by Megan Meyer

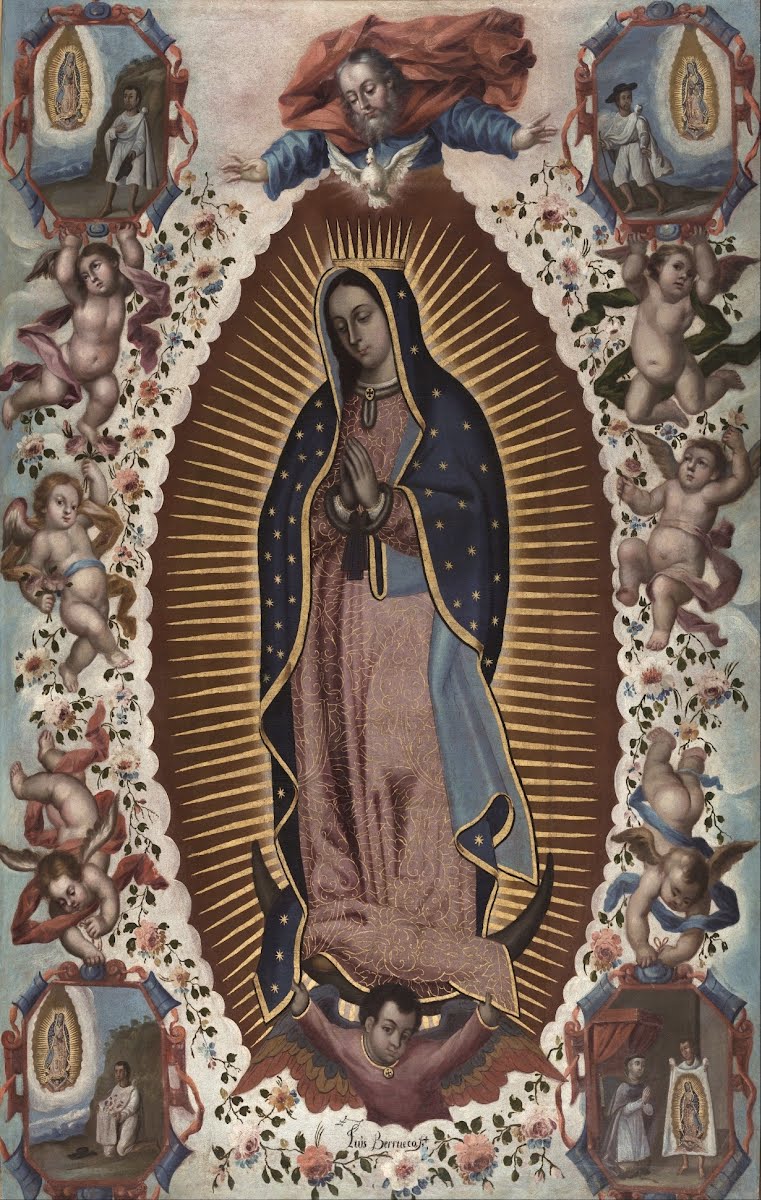

Right: Virgin of Guadalupe, Luis Berrueco, mid 18th Century, 81 ¾ x 56 ¼ inches, VMFA

In this paper, I will be analyzing and comparing two works from the viceroyalty of New Spain: the Virgen de Guadalupe by Luis Berrueco (mid 18th c.) at the Virginia Museum of Fine Art and the Feather Miter (16th c.) at the Museo del Duomo in Milan. My paper will first take a formalist approach to analyzing these pieces in a purely visual context, then a postcolonial approach, focusing on the aesthetic dimensions of these pieces that acknowledge cultural hybridity between Spanish and indigenous Mexican artworks. I will be arguing that there are distinctive similarities in the way that these pieces were influenced by European and indigenous cultural exchange.

Virgen de Guadalupe

A woman, the Virgin of Guadalupe, appears in the center of the painting surrounded by rays of light and scalloped clouds. There is a strong emphasis on roses in this painting, as they surround the halo of light that radiates from the Virgin. Directly above her, a man releases a dove, while directly below, a baby with eagle wings grasps at the cloak and dress of the Virgin. In the four corners of the painting are four vignettes which describe a narrative unfolding. To the Virgin of Guadalupe’s left and right are six putti – cherub like angels – that interact with both the surrounding roses and the four narrative cartouches.

Rays of sunlight emanate from the Virgin, but twelve beams crown her head. A crescent moon is beneath the feet of the Virgin. The skin of Guadalupe is darker than canonical depictions of the Virgin Mary – she is an indigenous representation of the virgin mother. The Virgin clasps her hands in prayer, and bows her head to the right. She is a pious Christian as well as a devoted mother.

This painting of Luis Berrueco’s Virgin of Guadalupe conforms to the traditional conventions of depicting the Virgin. A great deal of the visual iconography of the Virgin of Guadalupe comes from descriptions of the Woman of the Apocalypse from the Book of Revelations. In this biblical text, the Woman of the Apocalypse, often thought of as the Virgin Mary, is a protagonist in a war between the angels and the dragon (understood as Satan) who desires to kill the child of Mary. Like Guadalupe, Mary is described as surrounded by sunbeams, standing on a crescent moon with a crown of twelve stars on her head. The crescent moon at the Virgin’s feet is a symbol of the perpetual purity and immaculateness. The crown of stars could refer to a number of things – the twelve apostles, twelve tribes of Israel, or the twelfth chapter of the Book of Revelations, from which the Woman of the Apocalypse appears.

The narrative vignettes tell the story of the Virgin of Guadalupe appearing as an apparition to the Christianized Nahua man Juan Diego. In the first panel, she speaks to him in Nauhatl, instructing him to call upon the local archbishop to erect a church for her. In the second panel to the top left, she instructs Juan Diego for a second time. In the third panel to the bottom left, the Virgin of Guadalupe appears as an apparition for a third time, ordering Juan Diego to collect roses in his tilma to present the flowers to the archbishop. In this panel, flowers pile up on the tilma of Juan Diego. In the fourth and final panel, Diego unfolds his cloak to reveal the Virgin of Guadalupe etched on to his tilma. In this vignette, the bishop, overcome with the miracle, clasps his hands together in prayer. The painting is representative of a Christian miracle on Mexican soil.

Paintings of the Virgin have a rich historical tradition, the original painting thought to have been made by indigenous artist Marcos Cipac in 1556. The miraculous status of this image became so venerated, it is considered by many an acheiropoieta – divinely created, made by the hand of god. This original painting set a distinctive precedent, with many artists replicating this image as devotion to the Virgin proliferated throughout Mexico. Painted renditions are thought of as being touched to the original, transferring the power from the original tilma to successive paintings. Subsequent artists determined ways of distinguishing their renditions from the original’s acheiropoieta form. Baltasar de Echave Orio painted the tilma of Diego with three dimensionality while painting a two dimensional Virgin fixed to the cloak, documenting this otherworldly miracle on the earthly fabric. Juan Correa stressed the painting of flowers to demonstrate his ability of handling pigment and color, and to stress his knowledge as an artist. In this painting, Luis Berrueco is drawing from the historical conventions of depicting the Virgin of Guadalupe, while diverging in a few ways. The first way is in the depiction of the putti, which are depicted as playful and almost mischievous. The second way this painting can distinguish itself is in its dramatic size, measuring in at 82 x 56 inches.

In order for a miracle, such as the one of the Virgin of Guadalupe, to be accepted by the church, it must be approved by the Vatican. Increasing public veneration for the Virgin of Guadalupe throughout viceroyalty of New Spain forced the hand of the Vatican and the church to acknowledge and give credit to this miracle that occurred on Mexican soil. This painting can be seen as a symbol of indigenous and European exchange, as it is the product of cultural hybridity. As a devotional image, she is a national symbol of Criollo and Amerindian pride, a nationalist image which embodies inclusivity, divine grace, and bounty for the homeland of Mexico. The Virgin can be thought of as a representation of Latin American identity. While she reflects a diverse yet conflicted Colonial past, she is also a representation of an independent present.

Feather Miter

Miter, New Spain, 16th c., Feather mosaic, agave paper, linen, silk, metal thread, Museo del Duomo, Milan

The feather miter, from 16c. New Spain, is made up of the miter (the headpiece) and the vimpa (the shawl draped over the shoulders of the bishop). The piece is extremely rich and decorative, filled with religious symbology. The miter depicts the crucifixion of Christ. There are interwoven letters, where the interior of the letters depict scenes and characters from the passion of the Christ, as well as various Arma Christi. Christ appears crucified in the central stem of the letter M. Within the left stem of the M character, is a praying mother Mary. Below her is the holy lance and sponge. To the right is another depiction of Mary, with the ladder used for the deposition below.

In the letter H, evangelists and disciples can be found within the body of each letter, including the betrayer – Judas, and the denier – Peter. At the highest point of the miter is God, who raises one hand in benediction, the other holding a golden cross. Below God flies a dove, and other various angels and heavenly figures. The vimpa is also extremely ornate, with curling botanical decoration. The design of the vimpa is very symmetrical, with rich reds, greens, yellows, and blues that compliment the color scheme used within the miter.

Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, Lombard, Late 15th–early 16th c., Woodcut, Archivi Storici Diocesani, Biblioteche Storiche, Udine

The original source material for the feather miter, is a devotional image from the late medieval period that depicts the crucifixion of Christ through and interlacing of the letters MA and IHS. IHS refers to Jesus and MA refers to Mary. This miter, however, use their own artistic license in the depiction of the arma christi, which appear to have been shifted around and moved out of their initial alignments. The scenes and instruments of the Passion of Crist in the original woodcut were depicted in chronological order, which tells a cohesive narrative of the crucifixion of Jesus. Across all the miters that reference this original woodcut, there are small idiosyncrasies, inserted scenes and elements, that introduce uniqueness to the design.

Sacred Tree, altar, Mexico, Late Postclassic (1325-1521), Basalt (from Chalco), Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City

Along with their depictions of Christian iconography, the amantecas working on the miters introduced pre-Hispanic pictographic traditions as well. For instance, rather than simply mimicking the acanthus leaf, the feather workers deviated from their original source material to create a visual hybrid. From an iconographic viewpoint, the botanical elements of this piece have stronger ties to certain stone works from the late postclassic period in Mexico..

These feather pieces were extremely valuable in Europe, appreciated not only as the treasures of colonial conquest, but because of their uniqueness and natural rarity. Feather paintings were not just exoticized, but highly appreciated. The magnificent luminosity of the feathers would have lent themselves to religious performance when worn in a liturgical space. As the surface of the miter and vimpa was made with iridescent feathers, when in motion, the feathers created a dynamic relief that reflected and moved light creating an aura which would have moved anyone with its shimmering display.

The Feather Miter, and other related feather miters, was a combination of both European and indigenous pictorial languages. Of course the miter reflected Christian iconography, but was created by indigenous artists who incorporated their own iconographic symbolism and subtlety to these pieces. From an iconographic perspective, this feather mosaic bears traces of cultural identity from both sides – Spanish and indigenous.

Concluding Thoughts

Luis Berrueco’s Virgen de Guadalupe takes its original inspiration from a biblical story, and is a representation of the Christian figure of Mary, but she is Mexico’s patron saint. The Virgin of Guadalupe has come to represent and enshrine inclusion, nationalism, and Latin American identity. The Feather Miter, of course, is representative of a Christian, European woodcut, but was executed by indigenous amantecas who introduced nuance, originality, and pre-Hispanic iconography to their Westernized feather paintings. The context behind both Luis Berrueco’s Virgen de Guadalupe and the amanteca’s Feather Miter is dynamic and unique. Where there is interaction, hybridity is what follows, and this can definitely be seen in these two works, which have been shaped by European and indigenous cultural exchange.

Bibliography

Alexander Bailey, Gauvin. Art of Colonial Latin America. 2005. New York: Phaidon Press Limited, 2005.

Russo, Alessandra , Wolf Gerhard , and Fane Diana. Images Take Flight. 2015. Hirmer, 2015.

Wolf, Eric R. “The Virgin of Guadalupe: A Mexican National Symbol.” The Journal of American Folklore 71, no. 279 (1958): 34–39.