by Henry Xie

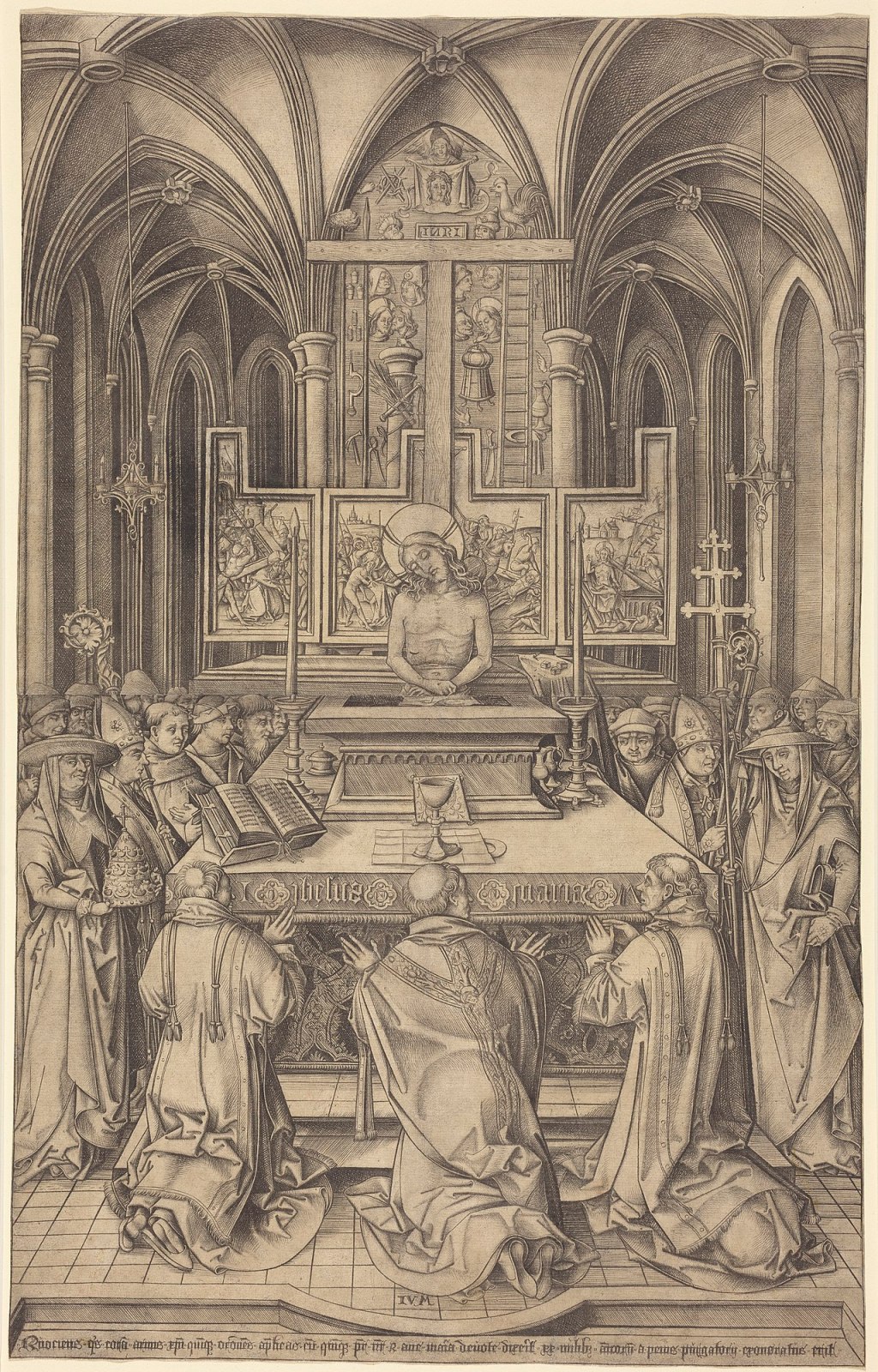

Right: Mass of Saint Gregory, 1490/1500, Israhel van Meckenem, German, Engraving, 18 5/16 × 11 9/16 in.

After the Spanish conquest and the establishment of New Spain, art in America experienced dramatic changes. The forced adoption of Catholicism and European art styles were both used as tools to sustain the Spanish rule and synchronize the worlds across the Atlantic. Though they have influenced New Spain tremendously, and such enforcement often led to the belief that indigenous artists were mere copiers of European arts, they never completely ruled out the native elements before the conquest. On the contrary, the originalities of New Spanish art are often obvious when seen side-by-side with their European inspirations. By comparing two well-known artworks from sixteen and seventeenth-century New Spain, the Mass of St. Gregory by an unknown amenteca and The Triumph of the Church by Cristóbal de Villalpando, to their sources of inspiration, both examples present strong evidence that indigenous artists created their work with originalities.

Mass of Saint Gregory, 1539 CE, Mexico City, Nahua, Feathers, gold, wood, pigment, 26 3/4 × 22 1/16 × 7/8 in.

Customized designs in the Mass of St. Gregory

The injection of Christianity in New Spain has created some of the earliest artistic mixtures between the Old and New World, and feather mosaics, with the Mass of St. Gregory, dating it to1539, is arguably one of the oldest pieces of evidence resulting from the drastic changes. Feather mosaics are a traditional art from Mesoamerica, created for a wide variety of purposes, from headdresses to shields, to clothes, and religious purposes. However, the Spanish colonizers completely banned the worship of indigenous deities and anything considered to be related to “pagans”. Instead, the Christian doctrines were introduced and feather mosaics were transformed into a powerful medium for spreading the new ideology.

The practice of feather mosaic has always been considered sacred, even before the arrival of the Spanish. Because many Aztec deities, such as Huitzilopochtli and Quetzalcoatl, had significant bird features, feathers were believed to be links to the gods and carry special power. Fortunately, the art form itself was retained, and the consecrated material is now used for worshiping Christian figures. In 1523, Pedro de Gante, among twelve Franciscan monks, was sent to preach in New Spain by Pope Clement VII. De Gante believed that there were not enough imageries in New Spain for spreading the faith, and he created the Escuela y Talleres de Artes Mecánicas, an atelier where Amentaca, the feather artists, were instructive and supervise to work exclusively on Christian iconography, based on European prints.

The Mass of St. Gregory, dated to 1539 from the inscription, is currently the oldest feather mosaic with a Christian subject known to us. It was created in Escuela y Talleres de Artes Mecánicas, supervised by the Franciscan monk himself. The inscription also suggests that the mosaic was a gift to Pope Paul III, possibly used for thanking him for the papal bull which he declared all natives were capable of conversion and spoke against enslavement. The image depicts the miraculous event when Pope Gregory had a vision of Christ during mass. He saw the bread turning into the body of Christ, and the Man of Sorrows appeared before him. The event proved the belief in Catholicism about transubstantiation, that the host would literally turn into the body of Christ during the consecration.

Mass of Saint Gregory, 1490/1500, Israhel van Meckenem, German, Engraving, 18 5/16 × 11 9/16 in.

Because of the subject, the Mass of St. Gregory was a popular subject, and the feather mosaic was likely based on a print with the same name, created by German printmaker Israhel van Meckenem. Both images follow the late medieval style depiction of the event, where the altar is shown with a frontal view. The vision of the wounded Christ appears right in front of the altar at the center of the composition, and the pope is kneeling and praying under him. Judas appears on one side with a money bag, and an angry man is spitting on Christ on the other. The figures are then surrounded by symbols that signify his suffering, such as the spear, the whip, and the sponge that was used to feed him vinegar.

However, the feather mosaic of the Mass of St. Gregory is not an exact copy of its source material. The most obvious difference is the media: instead of a monochromatic print, the amentacas used iridescent feathers– they replicated these intricate designs by first carefully gluing feathers together on a sheet of amate paper, and by cutting the paper into small pieces, the amentacas were able to create soft transitions without being limited by the anatomy of feathers. In fact, the texture of feather mosaics can be so smooth, it is said that Pope Sixtus V wanted to touch a mosaic of St. Francis of Assisi to make sure that it was not painted.

Immaculist Tree of Jesse, 16th century, Feather mosaic on the backside of an episcopal miter, Toledo Cathedral, Toledo, Spain

The difference doesn’t end here. If we look carefully, we may discover that a pineapple– a fruit unknown to Europe before the discovery of America– was placed on the sarcophagus of Christ. This is a sign that indicated the indigenous artist’s understanding of the source material, and rather than copying the same image, they created a localized version. A similar result can be seen in other examples as well. For instance, several feather miters depicting the Tree of Jesse were created as gifts and sent to Europe. All were based on a print from the Book of Hours, yet each miter had unique characteristics: some species of trees were different, and some included animals that were native to America. On one hand, this could be because it was unrealistic to create identical reproduction through such a different medium; on the other hand, this meant that feather works were sometimes customized, and the original compositions were reinvented rather than copied. And because of this, many considered feather mosaics as a form of painting, rather than a craft.

Cristóbal de Villalpando’s reinvention of painting

Cristóbal de Villalpando, The Triumph of the Church, 1686, Mexico City’s Cathedral, Mexico City.

The inclusion of originality does not end with feather mosaics but was carried on throughout the art of New Spain. One of the most well-known cases was Cristóbal de Villalpando. Villalpando was born in New Spain, sometimes known as the student of Baltasar de Echave Rioja. His paintings often come in large scales, with a vivid color palette, deep contrast, and a strong narrative. Because of these reasons, he was often compared to Rubens, who was known to be one of his main sources of inspiration, as well as neo-Venitian artists in Spain.

Villalpando, as well as most artists trained in New Spain at the time, took inspiration from the prints that were made in Europe. One of the notable examples is the monumental fresco, The Triumph of the Church, located in the Metropolitan Cathedral in Mexico City. Here, the artist painted the chariot of St. Peter crushing all that’s evil and pagan. On the bottom right, we see St. Peter sitting below Hebrew writings that remind people of the presence of God, accompanied by the personification of the Holy Spirit, who is in red, with a dove on her chest. In the center, we see a female figure in white, who is the personification of Faith or Eucharist, holding a chalice and a cross. Above her, the papal crown and a key represent St. Peter. On the bottom left, the Virtues appear to be leading the chariot that is crushing evil and paganism. On the top, the artist painted writings signifying the papal power on one side, and the Assumption of the Virgin on the other.

The Triumph of the Church, Peter Paul Rubens, c. 1625, Museo del Prado, 25 x 41.3 in.

It was believed that Villalpando’s The Triumph of the Church was based on a composition of Peter Paul Rubens. Interestingly, Rubens’s design was supposed to be made into a tapestry, and it is said that Villalpando has never seen Ruben’s work in person. Therefore, it was likely that the artist based his painting on a version of engraving circulated in New Spain. However, much like the amentecas, Villalpando did not simply reproduce the design but heavily remodeled it. He modeled his design after no less than four European sources: the concept was largely based on Rubens’s The Triumph of the Church through the Eucharist; the chariot and horses were pulled from Rubens’s Laurea Calloana; the baldachin and Faith were taken from a print of Flemish artist Maarten de Vos; and lastly, the architecture in the background is based on another Flemish artist, Abraham van Diepenbeeck’s Thesis Sheet of Claudius von Collalto.

And yet, the final result of Villalpando’s painting is distinct from all other compositions of the same subject. Aside from the dynamic motion, the grandness in scale, and the precise execution that were unreachable by most artists around his time, the careful selection of his model could not be overlooked. It suggests that Villalpando was not only capable of delivering a high level of artistic accuracy but also expressing his own artistic philosophies. Much like the European art academy system, which believed that artists had to copy Old Masters’ work over and over again before creating their own style, Villalpando’s familiarity with his European source material would have made him a master of art in the New World.

Comparison and conclusion

From both the example of Mass of St. Gregory and The Triumph of the Church, the originalities of artworks in New Spain were apparent. Furthermore, the appropriations performed by artists in the Viceroyalty often create something beyond its inspiration: the Mass of St. Gregory combined Christianity with pre-Conquest rituals, depicting Christ as both the preacher and the sacrifice; as for Villapando, he was well known for his new originals based on European prints, which he took great pride in. In the last painting of the commission cycle from the Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral, he signed “Cristóbal de Villalpando Ynventor”, or identifying himself as an inventor of images, rather than a creator. However, the question of originality can always be debatable yet meaningless at the same time, since the comparison between the Viceroyalty and Spain is not fair considering the recourse and political climate. Finally, if the papal bull from the 16th century has already declared those who live in America had the same soul as others, the normalcy of European originality shall not be encouraged in the present day.

Bibliography

Göttler, Christine, and Mia M. Mochizuki. The Nomadic Object: The Challenge of World for

Early Modern Religious Art. Leiden: Brill, 2018.

Hyman, Aaron M. “Inventing Painting: Cristóbal De Villalpando, Juan Correa, and New Spain’s

Transatlantic Canon.” The Art Bulletin 99, no. 2 (2017): 102–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2016.1249251.

Massing, Jean Michel. “Prints and the Beginnings of Global Imagery.” The Reception of the

Printed Image in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, 2020, 264–90. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003029199-18.

Olson, T. P. “Reproductive Horror: Sixteenth-Century Mexican Pictures in the Age of

Mechanical Reproduction.” Oxford Art Journal 34, no. 3 (2011): 449–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxartj/kcr041.

Pierce, Donna, Rogelio Ruiz Gomar, and Clara Bargellini. Painting a New World: Mexican Art

and Life, 1521-1821. Denver, CO: Denver Art Museum, 2004.

Rocha, João Cezar. “The Poetics of Emulation in a Latin American Context.” Transnational

Perspectives on the Conquest and Colonization of Latin America, 2019, 156–67. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429330612-13.

Russo, Alessandra, Gerhard Wolf, and Diana Fane. El Vuelo De Las Imágenes: Arte Plumario En

México y Europa = Images Take Flight: Feather Art in México and Europe. México, D.F.: Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, 2011.

Russo, Alessandra. “Plumes of Sacrifice: Transformations in Sixteenth-Century Mexican Feather Art.” Res: Anthropology and aesthetics 42 (2002): 226–50. https://doi.org/10.1086/resv42n1ms20167580.